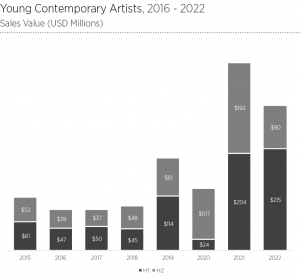

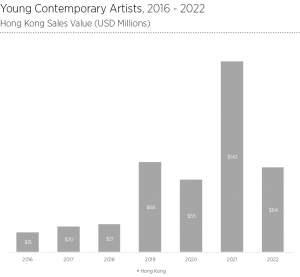

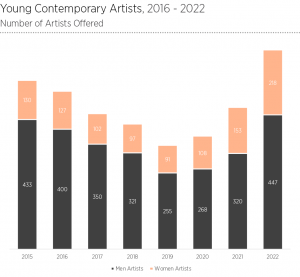

Could economic uncertainty fuel further interest in art investment this year? Or are we reaching the tail-end of the post-covid art sales boom?

With inflation in many developed countries running the risk of entering into double digits, and with the post-Covid economic recovery stalling, turbulence has been felt in financial markets in recent months. S&P 500 is down 23% from the beginning of the year, and the more tech-heavy NASDAQ index has dropped 32% in the same period. Even the crypto market has failed to provide a safe haven for investors in recent months, as Bitcoin prices have dropped from more than $61,000 from its peak in October 2021 to around $20,000 today, a fall of 67%. The Economist reported last week that the overall crypto market had plummeted from its peak of $3.2 trillion in November 2021 to less than $1 trillion today.

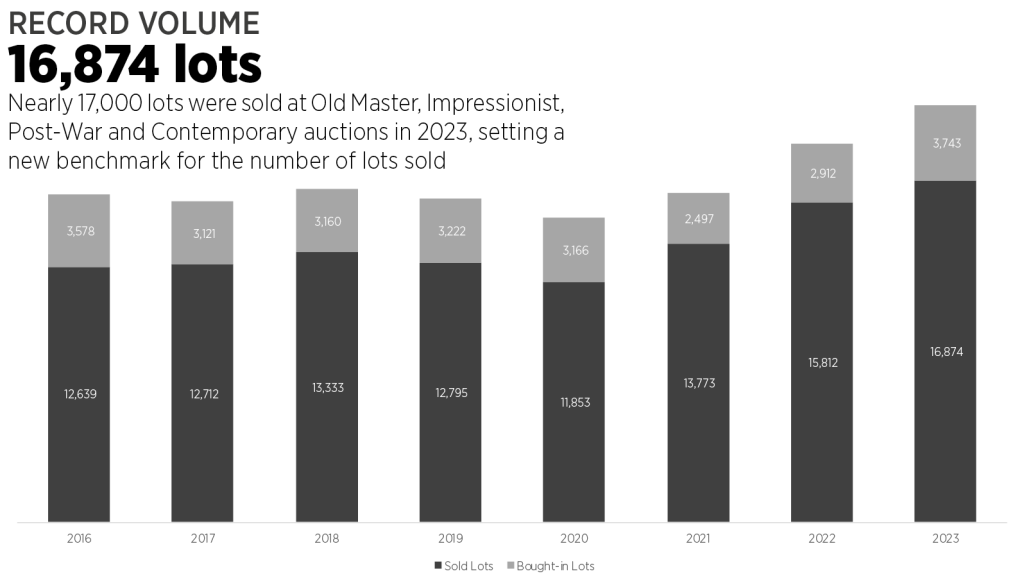

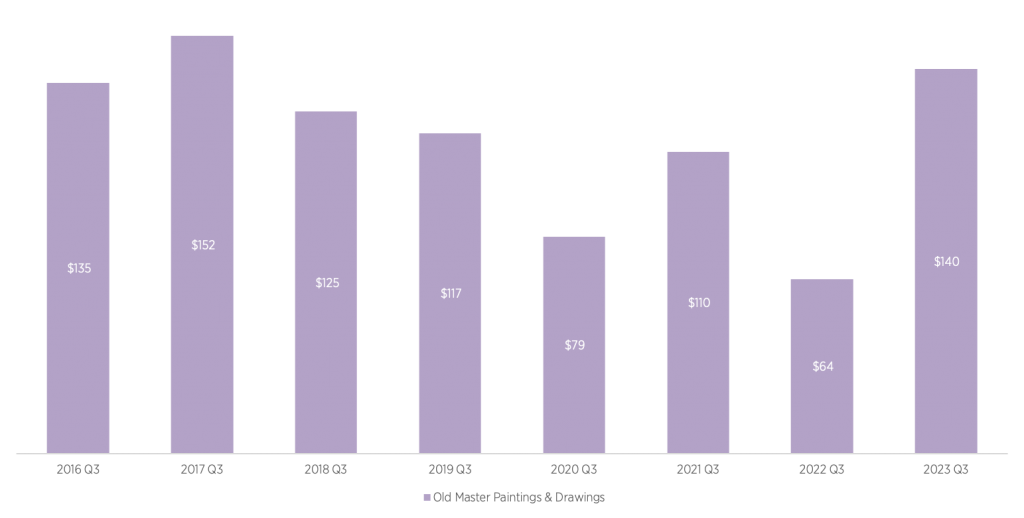

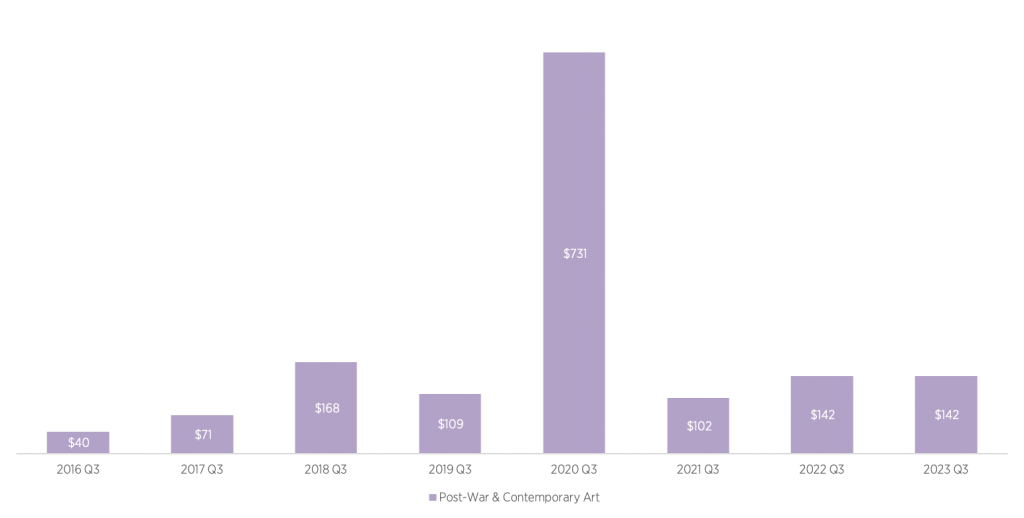

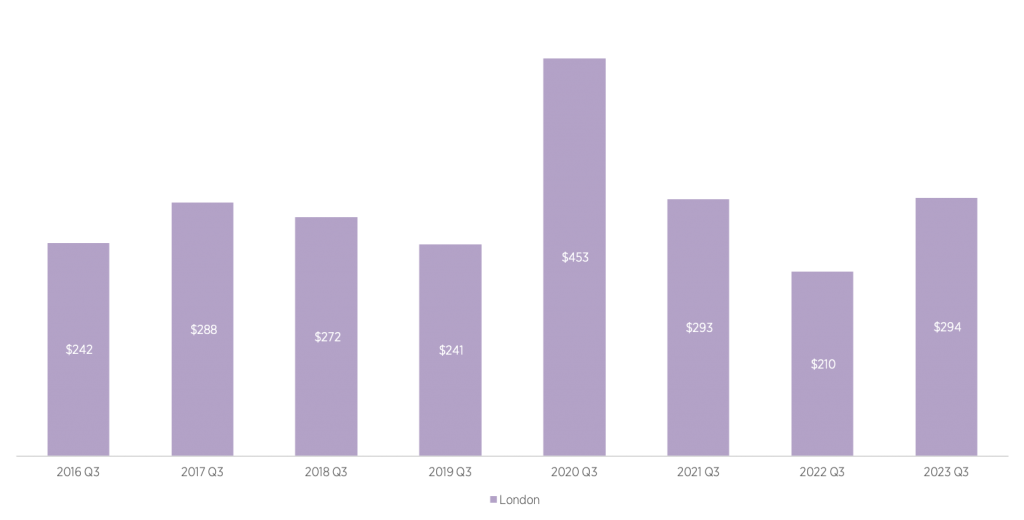

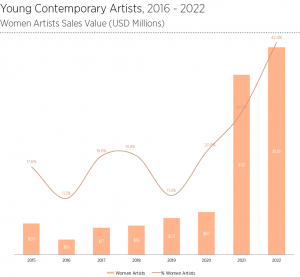

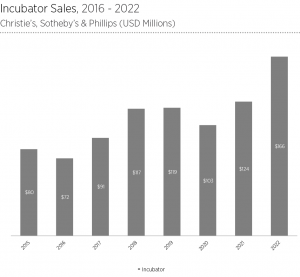

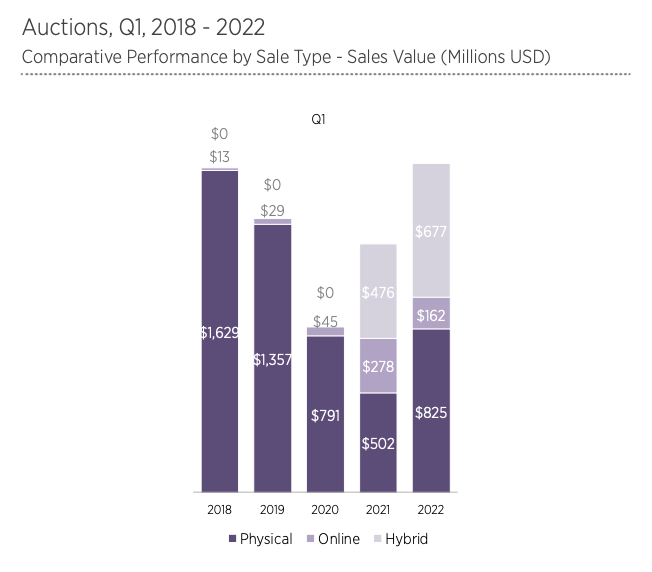

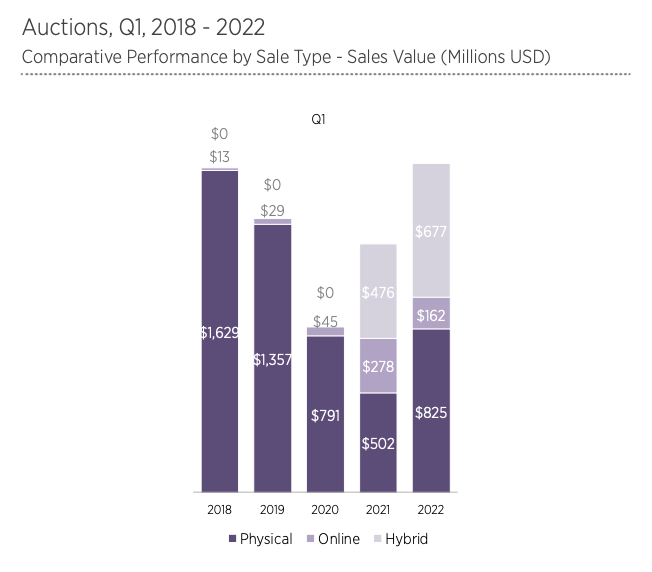

So how has the art market reacted to the bad news this year? Surprisingly well so far. Q1 public auction figures from Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips were up 32% year-on-year from 2021, and Q2 is also set to come in above last year (with sales figures up 28.3% so far, not counting London’s Marquee auction week later this month). But can the art market withstand the reality of the deteriorating economic situation, and if so for how long?

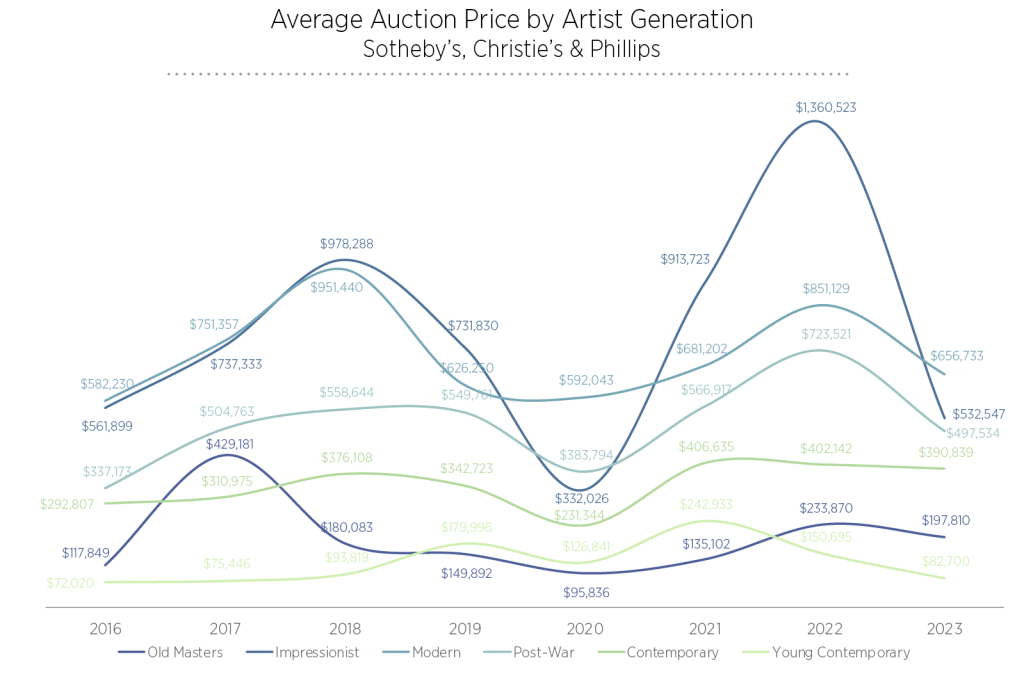

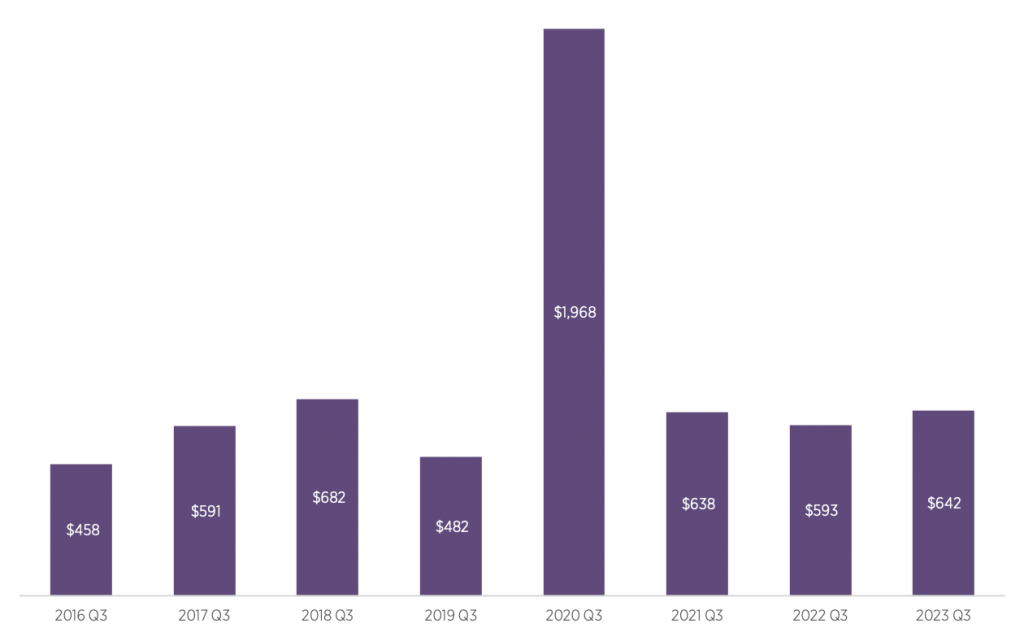

Source: ArtTactic

Why fractional ownership in art?

New models of regulated investments in art are emerging, with the concept of ‘democratising’ art investment becoming increasingly popular over the last two years.

Access has always been a big hurdle in the art market. Firstly, the price inflation in the art market over the last 20 years has moved investment-grade art out of reach for most collectors and investors alike. Secondly, unless you are an insider and well-connected in the art world, the art market can often feel impenetrable and intimidating to those on the outside. Asymmetric information and lack of transparency are frequently mentioned as key challenges. Thirdly, the unregulated nature of the art market also scares many potential investors, and although the recent introduction of anti-money laundering regulations in the EU and US are likely to help professionalize and modernize parts of the art market in coming years, there is still a long way to go.

In this editorial on Fractional Ownership of Art, I will explore this phenomenon in more details, and hopefully shed some light on the past, present and future of this evolving investment practice.

Fractional Ownership — An old idea whose time has come?

The concept of investing in art for purely financial purposes isn’t new. The early generation of art investment funds, from the British Rail Pension Fund in 1974 to the Fine Art Fund in 2001, have attracted interest among investors looking for higher yields and diversification benefits from alternative assets such as art and collectables. The fractional ownership model we see today is simply an extension of the same desire to democratise access to the art market, and the opportunity for the art market to tap into a new type of client base.

The term fractional ownership originally became popular for business jets. Richard Santulli of NetJets pioneered the concept in 1986, allowing businesses to purchase shares in a jet to reduce costs. This concept was later introduced to the property industry in the U.S in the early 1990s. These first fractional developments focused on real estate in the Rocky Mountains ski resorts, recognising that people did not want to buy whole homes, which they would use only for a few weeks a year.

Market Cycle #1

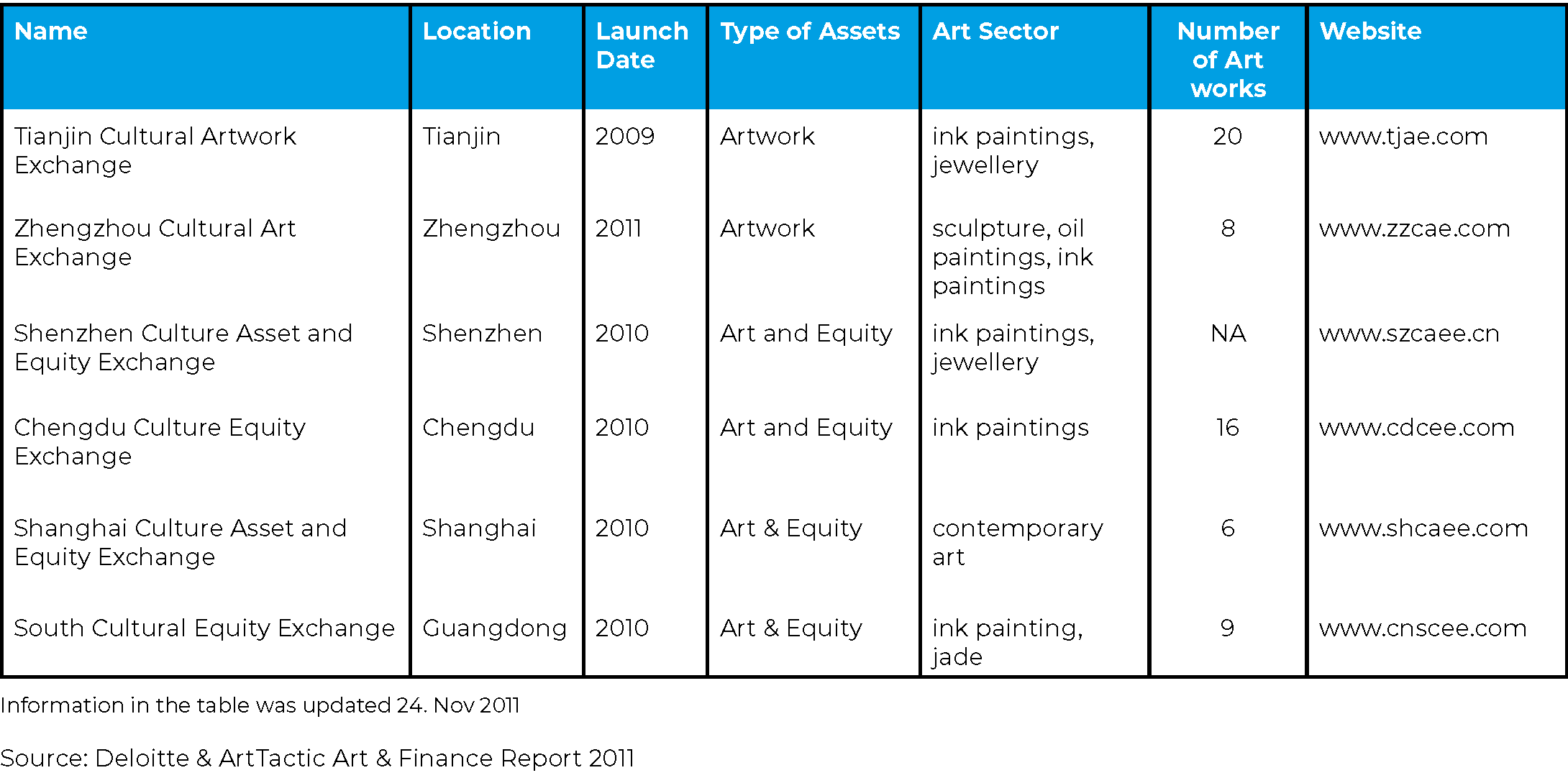

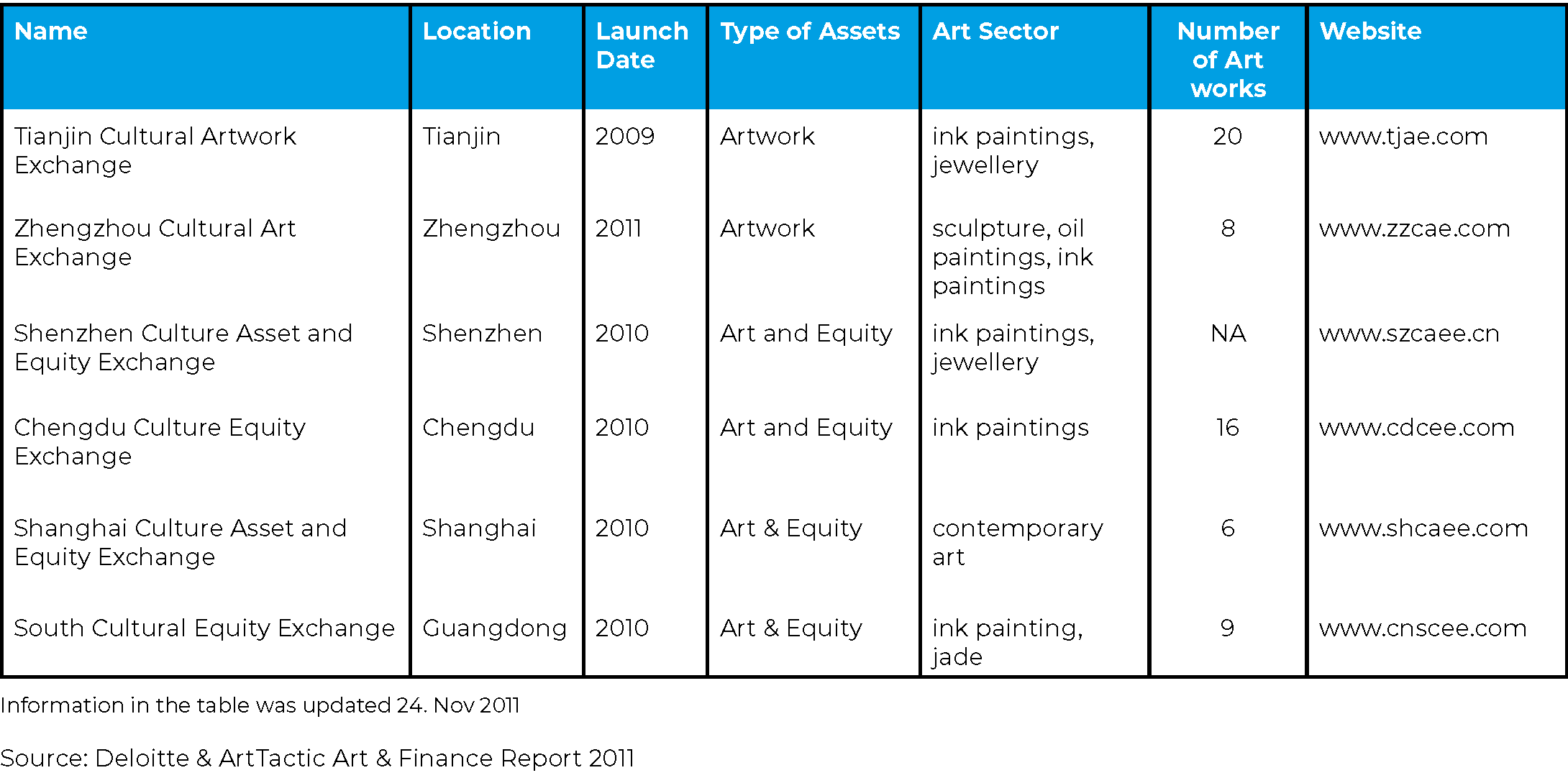

The emergence of fractional ownership in art started just after the financial crisis in 2008. Between 2009 and 2012, the rapidly growing Chinese art market, fuelled by government policies positioning the cultural industry as one of the key drivers for economic growth in China, created the ideal conditions for a new financial product built around the red-hot Chinese art market. These early fractional ownership models were known as Art and Cultural Exchanges and allowed investors to buy shares in artworks that could then be traded on these exchanges. Below is a table from Deloitte & ArtTactic Art & Finance Report 2011, which shows some of these exchanges that were active in the autumn of 2011. However, large price volatility and speculative behaviour led the Chinese authorities to impose restrictions on these exchanges in 2012, forcing most of these to close or transform themselves into something else.

However, similar fractional ownership platforms also emerged in Europe at the same time. With the entrepreneur Pierre Naquin setting up A&F Markets in Paris in 2011, and SplitArt announcing the same year that they were setting up an art exchange in Luxembourg, that would allow qualified investors to invest in shares of valuable artworks. For different reasons, both of these platforms failed to succeed.

Market Cycle #2

It would take another 6 years before the concept of fractional ownership in art started to re-emerge, this time on the back of the boom in crypto-currencies and ICOs (Initial Coin Offerings). The Singapore-based Maecenas raised $15.38m through an ICO in 2017 and the firm sold 31.5% of Warhol’s 14 Small Electric Chairs (1980) in 2018. A number of other platforms were set up around the same time – Feral Horses, ArtSquare, Malevich, and Look Lateral, but despite the excitement around fractional ownership as a concept, the issue around regulation was always going to be a thorny issue.

In 2018, the regulatory issue finally seemed to have been resolved, when Masterworks launched its first SEC regulated fractional ownership product with Andy Warhol’s ‘1 Colored Marilyn (Reversal Series)’ from 1979. Although, it would take the company a further two years to gain traction, the company has now more than 120 artworks on their platform with an estimated value of more than $500 million, and is now the market leader in the fractional art investment space. The company raised a $110 million Series A round in October 2021, led by Left Lane Capital and joined by Galaxy Interactive and Tru Arrow Partners, valuing the company in excess of $1 billion.

The success so far has encouraged other companies to follow, and Mintus, a UK-based FCA regulated fractional ownership platform announced they were entering the market in April 2022. The company was founded by Tamer Ozmen, previously a senior executive at Microsoft, and is counting former Sotheby’s CEO Tad Smith and Brett Gorvy, Christie’s former Chairman and International Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art, on their advisory board.

Other regulated fractional ownership platforms have aimed to build their business on the back of the increasing interest in tokenization and the NFT market. Sygnum, a digital asset bank, and Artemundi, an art investment fund pioneer, partnered in July 2021 to tokenize Picasso’s ‘Fillette au béret’ painting. This marked the first time the ownership rights in a Picasso, or any artwork, were being registered onto the public blockchain by a regulated bank, enabling investors to purchase and trade shares in the artwork called Art Security Tokens (ASTs).

Fractionalization has also become increasingly popular in the NFT market as prices of many NFT collectables, such as Bored Ape Yacht Club and ArtBlocks have moved beyond the reach of most investors. Fractional.art is an example of one of these platforms.

Whilst Masterworks’ initial intention was to use blockchain-technology to record and track fractional ownership in artworks, in the end the company decided to go for a traditional off-chain approach, which was probably a good idea, as other companies that tried to introduce both blockchain and fractional ownership in physical art have not yet managed to achieve the same level of attention.

The Future

Based on a recent survey for the Deloitte & ArtTactic Art & Finance Report 2021, 21% of collectors said that they were interested in investing in art through a fractional ownership model, with a significantly higher, 43%, of collectors under 35 years old saying the same. The pandemic seems to have been a catalyst for changing attitudes towards art investment, and corresponds to the growth we have seen in both the art market and the fractional art investment industry over the last 18 months.

So will the boom in fractional art ownership continue?

As the emotional component of art ownership is largely stripped out when you invest in a share of an artwork, the investment behaviour is likely to mimic that of any traditional investment. Bull markets will attract more investors and bear markets will likely see investors running for the exit.

What does this mean for the fractional art investment market? The demand is likely to continue as long as the art market remains as robust as it is now. However, so far, the fractional ownership market has been in a honeymoon period, where the post-pandemic art market recovery has fuelled art sales and prices, and most fractional ownership investors are yet to experience the chill of a market downturn, where liquidity dries up and prices fall (yes, prices of art can go down!).

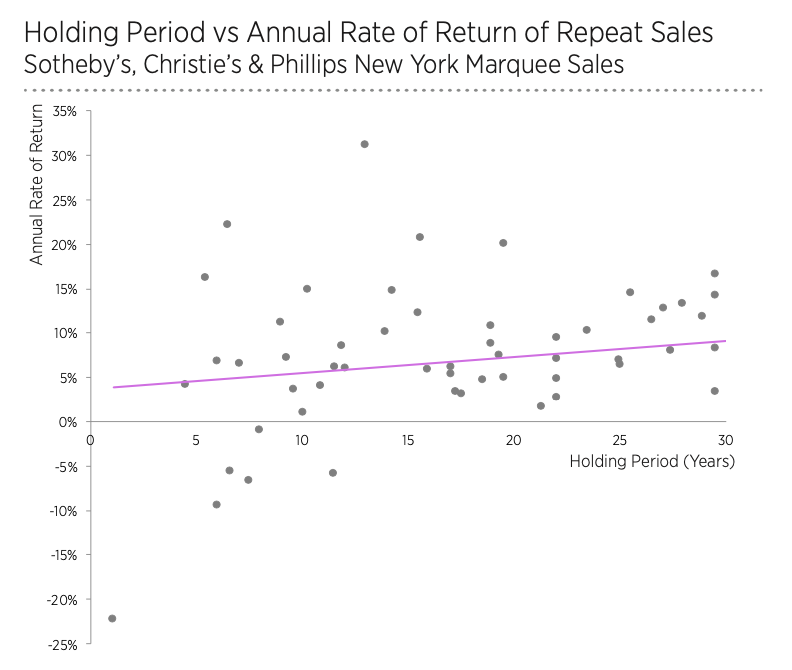

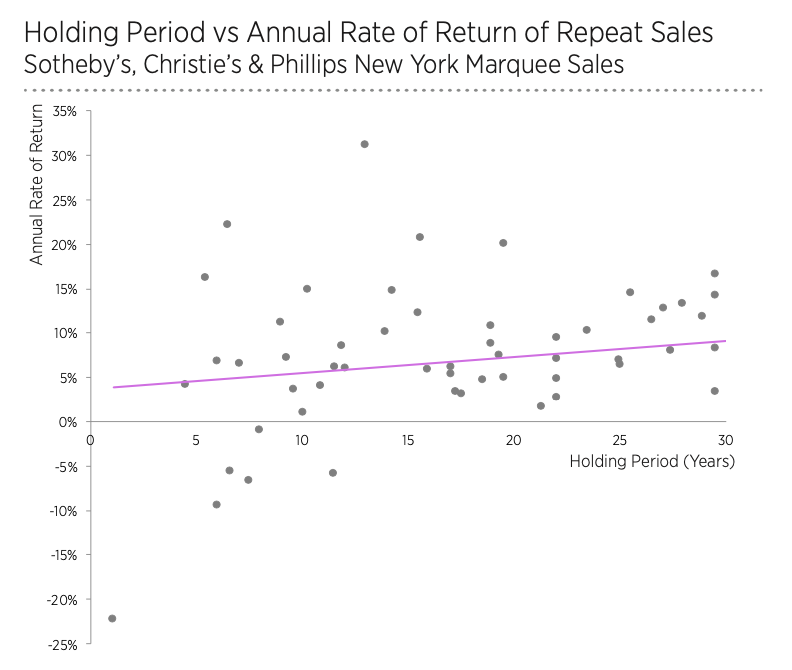

To make profit from art, the following ingredients are essential: expertise and knowledge, keeping costs to a minimum, good timing, access to inventory (preferably at below-market prices), access to buyers and the ability to take a long-term view and ride out any down-cycles. Those that were spooked by the financial crisis in 2008 and the pandemic in 2020, would have been better off sitting tight, as the art market showed strong resilience in both cases, and recovered within a 12–18 month period. Recent analysis by ArtTactic looking at artworks with repeat auction sales in recent New York Marquee auctions in May, shows a positive correlation between the amount of time the artwork was kept away from the public market and the return on the investment. Among the 50 lots kept away from the auction market between 10 and 30 years, 49 sold with a positive average annual return of 8.8% (not adjusted for inflation). However, artworks kept away from the market for less than 10 years showed a more volatile performance, with 5 out of 13 lots seeing a negative return (see graph below).

Source: ArtTactic

One of the main challenges for fractional investment platforms right now, is that they are acquiring art at price levels that are reaching a historic high, and if you add the transaction costs to this (i.e. buyer’s premium if bought at auction, fees for regulatory listings, management fees and share of profits, if any), art prices need to keep going up much further before investors can expect any profits. If this doesn’t happen, investors need to brace themselves for the long haul, and hope that history keeps repeating itself.