Image: Detail of Ed Ruscha, 20-20-20, 1962.

This summer, ArtTactic celebrates its 20th anniversary! To commemorate this milestone, we would like to take a moment to reflect on the success, challenges, and immense growth our company has experienced over the last two decades. Since ArtTactic’s genesis in 2001, the art world at large has undergone remarkable changes that have both influenced and been influenced by ArtTactic’s quest for market transparency. Traditionally, the art world has been defined by its opacity and the informational chasm dividing industry insiders and outsiders. Until the early 2000s, even those considered ‘insiders’ – namely art buyers and sellers – willing to do their due diligence, had a hard time finding the right market intelligence to inform their multi-million-dollar consumer decisions. This is exactly the asymmetrical gap in information Anders Petterson saw that led him to create ArtTactic in 2001 amid the data revolution – a movement that created sweeping and lasting change for the art market, not to mention the global economy.

After several years in the data-driven industry of financial services, Anders decided to apply the economic models, analytical tools and data-collection strategies he had accumulated, to the art market. Having spoken to many of his former colleagues about their lack of interest in art investment, despite increasing evidence of fine art’s enticing financial returns, he determined that it was largely due to a lack of knowledge and confidence as a result of not knowing how to access data, information, and research on the market. Thus, ArtTactic was born with the goal of creating more transparency in the art market through education and information.

Around the same time, data-providers such as Artnet and Artprice had launched online databases, which aggregate public auction results, in the pursuit of market transparency. Consequently, Anders saw an opportunity to build on these services by focusing on in-depth analysis and exhaustive summary of artists and their markets. While there was immediate curiosity from art world professionals and patrons alike, data-analytics remained an unfamiliar and unwelcome concept to many stakeholders in the industry. When asked why market data was initially dismissed by so many, Anders reflects, “At the time, decisions were not made on the basis of data and research, but on relationships, networks and trust.” Thus, an ‘outsider’s’ opinion – as Anders acknowledges – was received with some skepticism. However, over time, after witnessing the power of analysis and comprehensive market reports, critics began to realize the value ArtTactic could bring to the industry as a benchmarking tool.

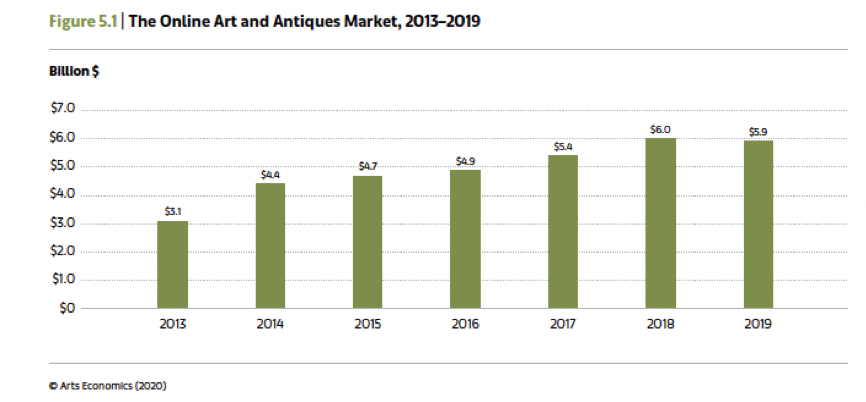

For Anders, a pivotal moment occurred in 2004 when he fortuitously met one of the world’s foremost contemporary art collectors in a lift during the ARCO art fair in Madrid. A brief conversation led to a second meeting in Miami later that same year, which would ultimately bear ArtTactic’s initial Art Market Confidence Report – launched in May 2005. To this day, Anders remembers the quote given to him by that encouraging collector, “[ArtTactic] is an idea whose time has come, the question is why no one has thought about it before.” His kind and supportive words spurred on the development of ArtTactic and in Anders’ expression, “kept [him] going for another 15 years.” Numerous other inaugural reports such as the first Art & Finance Report in 2011 in partnership with Deloitte, the Hiscox Online Art Trade Report in 2013 and the Art & Philanthropy report published in 2017, broke new ground and paved the way for transparency in new areas of the art market. Since those initial reports, the mechanics of ArtTactic – from the way we present information to the global reach of our network of experts – have changed and improved. However, the spirit of the initial reports and our guiding question – how can we use data to educate, communicate, translate and present to audiences beyond the traditional art world? – remains the same. More than ever, ArtTactic has faith in the power of data and visualization to broaden the art market, increase transparency and facilitate accessibility among stakeholders, both old and new.

Over the years, ArtTactic has maintained a small, productive and highly motivated team of art world professionals with diverse backgrounds. From the outset, Anders sought to foster a work environment that would allow people to develop their own interests and projects under the umbrella of ArtTactic. For instance, in 2009, Adam Green joined the company with the vision of creating an art industry podcast, which emerged as one of the first podcasts to discuss art market trends and has produced over 600 episodes to date. The free exchange of ideas has catalyzed some of the most pioneering and innovative features ArtTactic offers. Anders remarks on his philosophy, “In order to survive in a world of selling art market information, I believe in a small, agile set up;” the kind of set up where success and failure sometimes go hand-in-hand. “It’s become part of our DNA,” Anders admits when asked about how challenges and failures along the way have shaped the company, “I see failure as an integral part of our organic growth, and the only way to improve and find out what works.” It is seeing beyond market participants’ current needs and forecasting future needs that drives interesting and relevant research. By remaining self-funded and self-sustaining without external investors’ judgements for the sake of growth and scale, ArtTactic has always created space to take risks, experiment and innovate.

As we head into a new phase of the art market, defined by momentous change and uncertainty propelled by the global pandemic, data, information and research will become exponentially more valuable with time. While ArtTactic’s vision endures, our challenge will be adapting to support stakeholders as they transform and modernize their art businesses in the face of significant technological and demographical shifts.

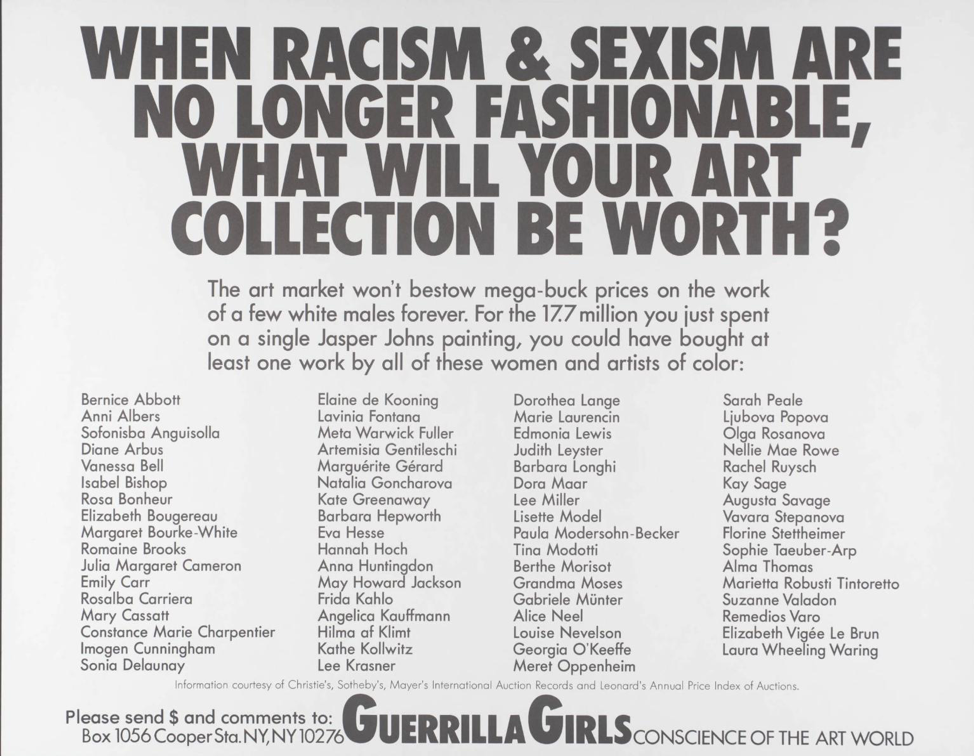

When asked about the next 20 years, Anders hopes to “continue the current momentum and enjoy the discovery of new research domains,” as well as “meet and collaborate with great people, and play our small part in making the art market a better and more exciting place to engage with.” In this next decade, we also see an opportunity for ArtTactic to focus more on inequalities in the art market and research new models of philanthropy aimed at finding solutions for creatives to develop sustainable practices both inside and outside of the traditional art market.

Finally, we would like to thank you – our loyal followers, contributors, and clients – for your continued support. Cheers to the next 20 years!