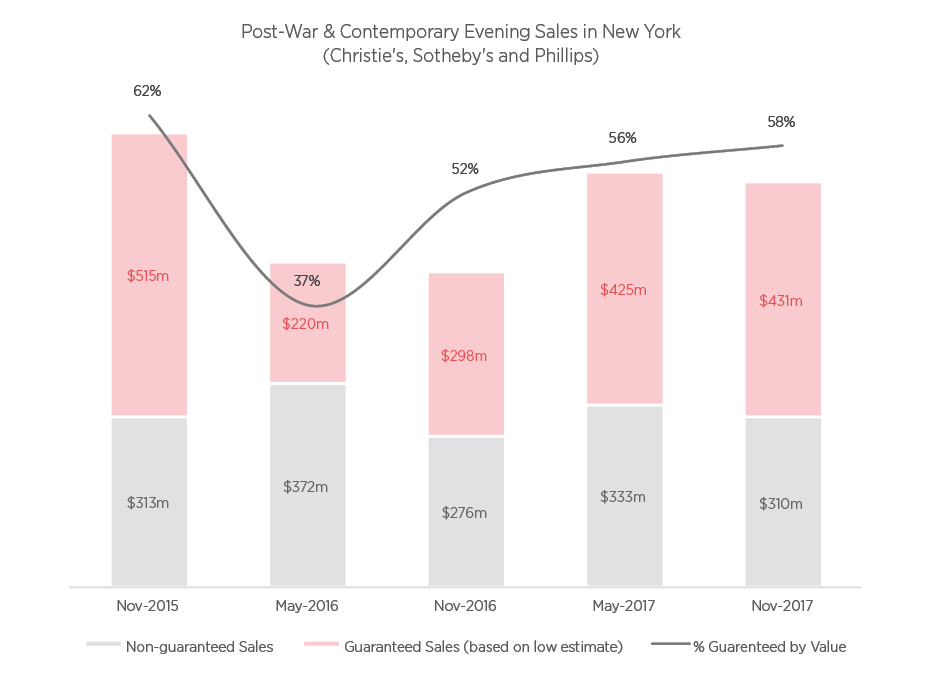

The graph shows the percentage of Guarantees by Value in Post-War & Contemporary Evening Sales in New York for Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips since November 2015.

Is the increasing level of auction guarantees a sign of art market confidence? Or is it a sign of investors and speculators feverishly chasing returns in a low-yielding environment?

In recent years, financial guarantees have played a pivotal role in the success of auctions and the sale of individual art works. Some have described these guarantees as anti-competitive, others as manipulative and a way of keeping prices artificially high. Whichever view one takes, financial guarantees have become an integral part of the auction landscape and a stimulus which the auction market seems to find itself increasingly difficult to wean itself off.

The highest grossing flagship auction sales, such as the Post-War and Contemporary evening sales, are now heavily reliant on the amount of money that has already been guaranteed (see chart). Essentially, the outcome of these sales are pre-determined by the market’s appetite for offering financial guarantees.

Let’s look at some of the stats. The upcoming contemporary sales next week in New York have an estimated $431million worth of guarantees (including the estimated $100 million painting by Leonardo da Vinci), accounting for 58% of the pre-sale low estimate value. This is a $132.9 million increase from last November.

Financial guarantees can have a huge impact on auction results. When Christie’s decided to pull back their financial guarantees in November 2015, offering an estimated $267 million worth of guarantees compared to $461 million the year before, the impact was felt immediatey. In the Post-War and Contemporary evening auction sale alone, their sales dropped from $751 million to $410 million in a single season.

Last month provided insight into what can happen when a high-value lot doesn’t carry a guarantee. ‘Study of Red Pope 1962. 2nd Version 1971’ by Francis Bacon was not backed by a guarantee and failed to sell at a pre-sale estimate of $60 million. Many experts considered this estimate to be exorbitant and way off the mark. The fact that the lot was not guaranteed suggests that guarantors are selective and reluctant to back lots that are not valued fairly. More importantly, it demonstrates just how dependent the top end of the auction market is on the backing of financial guarantors.

Financial guarantees seem to be good business practice, but it’s not without significant risk to the auction houses. There are many examples of auction houses incurring heavy losses due to financial guarantees. For example, 16 years ago, in November 2001, Phillips auction house (under the ownership of Bernard Arnault) incurred a significant loss when the Smooke collection sold for $86 million but reportedly carried financial guarantees of around $160 million.

More recently, in November 2007, Sotheby’s share price dropped 37% in one day, when their Impressionist & Modern evening fell way short of the market expectations. Two major guaranteed lots in the sale, Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Wheat Fields’ and Georges Braque’s ‘L’Echo’, failed to sell with pre-sale estimates of $35m and $20m respectively.

Only two years ago, in 2015, Sotheby’s gave an unprecedented $500 million guarantee to secure the collection of former chairman A. Alfred Taubman in competition with Christie’s. The transaction resulted in a reported $12 million loss in fourth quarter of 2015, and the announcement that Sotheby’s would eliminate the fourth quarter 2015 cash dividend. Although these losses were later reduced, it was far from a profitable venture for Sotheby’s.

So what are the auction houses doing to de-risk their exposure to guarantees? Third-party guarantees are becoming more common. In the November Post-War & Contemporary evening sales (across Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips), 29 lots out of 80 are guaranteed by a third party. Although these third party guarantees only account for 36% of the lots, they account for 56% of the value (based on the low pre-sale estimate). Although third-party guarantees reduce the risk for auction houses, the profit left in these transactions is diminishing as third party guarantors attempt to squeeze maximum profits from the transaction. The power that once belonged to the auction house has now shifted to the guarantors.

Why are the auction houses continuing this gamble? As things stand, they haven’t got much of a choice. Similar to premier league football, in order to participate in the top league, one must fork out hundreds of millions on players, with the hope that they will deliver results. The premier league of art auctions is a slightly smaller affair, with only Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips wrestling for the top global positions.

Phillips, the smallest of the three, has aggressively pursued market share by offering generous guarantees and financial incentives, forcing the two other houses to follow suit. In this market, where the sale of trophy lots is the only currency that seems to matter, perception is everything, and sellers will go with the house they see as the strongest or where the best financial incentives can be obtained. In the end, chasing consignments at the top end of the art market is a zero-sum game, and one auction house’s gain is another’s loss.

In the current hyper-competitive auction market, where auction houses are wrestling to convince sellers to depart from their treasures, financial guarantees have become an addiction that will be hard to shake.