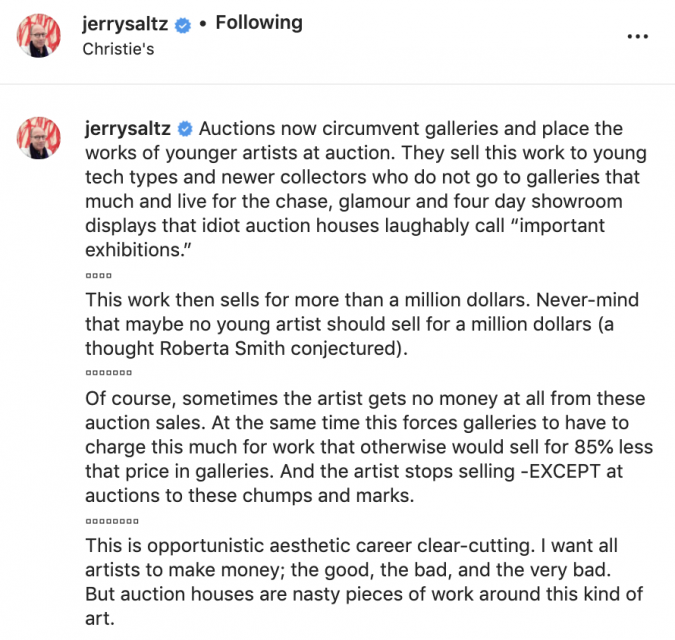

Jerry Saltz’s Instagram post from 23 November 2021.

Art critic Jerry Saltz took to Instagram to share his anger surrounding recent auction trends. In his post he marks auction houses as the enemy of young artists while galleries, undermined by auction houses, as a friend. This commentary seems shocking at first as auction houses can be a democratizing force in the ecosystem of the art world – allowing greater accessibility to buying art while also supporting more price transparency. The new buying trends at auction include a rise in young artists, female artists, and artists of color. While post pandemic changes can appear to be delivering on the calls for diversity in the art world, looking deeper, I question if these changing trends are really the benevolent forces that they appear to be.

During the pandemic, Art Basel’s 2021 Report found that the 2020 global art market was down 20% from 2019. The 2020 sales in London and New York fell 22% and 24% respectively. Lately, this downfall that took place in the height of the global pandemic is reversing itself. Auction houses are seeing great success following the pandemic. As collectors have had an increase of wealth, auction records are being broken at new rates. Blue chip artists are seeing new auction records and the contemporary art market is rising. In major marquee auctions, young and diverse artists are not only being increasingly featured, but experiencing skyrocketing prices.

The October evening sales in London — which brought in a total of £130.06 million, 27.1% more than October 2020 – were the first in person auctions in 18 months, an early indication to the success of the November sales in New York. Our research showed that total sales from Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips New York Impressionist, Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening auctions raised an impressive $1.95 billion, with total auction sales just 4.3% short of the record May 2018 sales. Half of the eight New York Evening auctions were white glove, and across all of the sales, only 11 lots were bought in.

The ArtTactic report, Post War and Contemporary Evening Sales evaluated the October evening auctions in London and found a rising demand and price for the work of young artists. Here, young artists accounted for 23% of the total sales value, almost double the year prior. Nine of the Top 10 performing lots (hammer price to mid-estimate) were by this generation of artists and 9 of the 13 auction records were achieved by them as well. The recent Marquee auctions in New York exacerbated the trends set by the London October auctions, as seen in our Marquee Evening Sales report. Here, younger artist’s auctions were pushed to record levels and guarantees reached a record high. The total sale value for artists under 45 was more than $58 million and the average prices of these artists were 84.7% higher than the prices seen last autumn. Our recent NextGen Report explored this rising success of these emerging forces in depth. These young artists had an impressive 185.5% increase in auction sales in the first half of 2021 and are seeing their wet paint sales (artworks sold at auction within 3 years or less of the creation date), on average, doubling their mid presale estimates. Overall, there is rising success and desirability surrounding these artists.

The Deloitte Art and Finance Report evaluates this growing demand for a younger generation of artists at auction. The change in buying trends could be the result of the rise in millennial collectors, who represent the highest spenders on art in 2020 (Art Basel). Some experts believe that this growing attention on a younger generation of artists “will likely benefit more younger artists of color, as well as young female artists that have traditionally been under represented” in the auction market. ArtPrice’s recent findings positively reflects this speculation – they found that the top five young artists (born after 1980) in the first half of 2021 were Matthew Wong, Avery Singer, Salaman Toor, Ayoko Rokkaku, and Amoako Boafo. These young artists and their recent auction success exemplify the strong and diversifying shift in what collectors are buying. Of these five artists, four of them are people of color, the other, Avery Singer, is a female. These artists hail from America, Canada, Pakistan, Ghana, and Japan reflecting a more global representation and display of artists at auction.

It is reassuring to see the rising prominence of a larger and more inclusive group of artists and seems as if change is coming from these auction results. Yet, evaluating these recent sales, there is cause for concern. Are the changing trends at auction truly supporting a diversified market? Or, could this dramatic shift cause more harm than good for both young artists and the market overall?

To better understand the cause and effect of the shift in post pandemic auction results, we must explore the latticed structure of the art market. Blue-chip artists and artworks are known to hold and steadily rise in value, despite market fluctuation. This is because they have established careers, critical acclaim, gallery representation, and strong exhibition history. Because of this, blue chip artists are sought after at auction and retain high prices. Auction houses, which function in the secondary market, seek to sell this work as they are motivated by profit. The auction houses have a responsibility to both their buyers and sellers; they are trusted to sell quality work for the best possible price that will also appreciate in value. The artist is lacking from this model and rarely profits from auction sales. Meanwhile, galleries mainly function in the primary market. They work with artists to sell their art and place it in collections, museums, and exhibitions which will overall positively affect and help to grow an artists’ market. The ecosystem of the art world has its weight distributed differently across each of its pillars, and young artists rely on galleries to uphold them. Helping support and develop their artists careers is a contributing factor to the opaque practices galleries operate upon. By not publicizing prices, galleries will never have to lower the price of an artist – something that is damaging to the career trajectory of an artist. Remaining exclusive in who they sell to can not only help land an artist in the hands of an important collection or museum, but also help avoid buyers who intend to quickly resell the work for profit (also known as “flipping”).

The market of a blue-chip artist is well established, and selling at auction won’t likely cause a negative disruption in their sales. This is not the case for young artists, who have not yet had the time or space to reach this same level of establishment. Their markets are still fragile, and any type of auction results, good or bad, can have an overall lasting and possibly detrimental impact. A positive auction result can lead to a negative result for the artist: price inflation at galleries and an unsustainable and speculative market that the artist must try to feed. The term “red-chip”, coined by Art Newspaper writer Scott Reyburn, applies to the current auction market and how “buyers continue to be only interested in the latest thing”. Reyburn sees the prices rising for an “ever-changing” list of “fashionable new names” such as these young artists. Deloitte’s report speculates that a driving force for this obsession with youth could be “collectors and investors looking for the next big thing” which would push these artists’ “prices far beyond justified limits, given the stage of these artists’ careers” which ultimately negatively impacts the artist.

The recent auction success of young artist Flora Yukhnovich provides insight into my fear of these auction results. Recently, her Rococo inspired work “I’ll have What She’s Having” (2020) sold for £2.2 million, almost 40 times its £60,000 low estimate at Sotheby’s Contemporary Art Evening Auction. Looking at this October auction, Art Price questions if her desirability stems from her being relatively unknown and therefore not on the books of prestigious galleries. This means that auction houses can offer her and similar young artists’ work without any price reference. In less than two years “I’ll Have What She’s Having” has already been sold twice; initially sold by Parafin Gallery to a private collector, and then resold by Sotheby’s. This work was essentially flipped, a tactic where speculative buyers quickly resell artworks for profit, and a tactic that could crash a young artists market. As Saltz sums up, “[Auction houses] now circumvent galleries and place the work of younger artists at auction” forcing galleries to raise their prices to reflect the market.

While these recent sales are helping gain attraction and attention to marginalized artists’ careers, it is done in an unsustainable way that could negatively impact the artist. These sales don’t purely represent support for a diverse market, but capitalize off of the artists. The buying tactics follow what’s in vogue, and can lead to harmful long-term results for the artists’ and an overall speculative market. Of course, this is not all buyers’ intention, and real change and desire is one underlying driver of the shift in trends that others are trying to profit on. But, to find lasting impact from this momentum, we must be critical and dig deeper, evaluating why these trends could be surfacing and what they implicate. Contemporary art is not solely a profit producing asset but a cultural commodity. As we see a growing and changing pool of collectors buying contemporary art, an artist-centered approach to buying must be reinforced. The shifting collector base must continue to seek out new, interesting, and diverse art without reducing it to “the next big thing”.