Imagine you are walking in Mayfair and you are attracted by a shiny window of one of the many world-class art galleries of the neighbourhood. You walk in, politely greet the front desk staff, ask for the press release, and then you finally start filling your eyes with some of the most representative artworks of our contemporary culture. Nevertheless, while you are wandering in the space, a burning question pops into your mind: how much will these artworks cost? If you are brave enough – or, maybe, I should say naïve – you might decide to ease the burden of your doubt and go and ask the gallery assistant, who is very likely to graciously smile at you and ask: are you already our client? This situation does not stand in the realm of the hypotheses, it is actually an incredibly common “protocol” adopted by most of the blue-chip galleries.

The lack of transparency of the art market is not a breaking news. However, a further distinction needs to be made between the primary and the secondary market. The opacity of the latter, indeed, has sharply decreased over the years due to the inception of price databases such as Artnet, the first company to gather and publish sales prices of auctioned artworks. Despite the success of its service amongst collectors, according to Artnet’s CEO Jacob Pabst, big auction houses and art galleries did not appreciate the mission of the company, which had to wait over a decade to finally become profitable, demonstrating that its aim was not to replace a system, but to enhance its operations. Conversely, the primary market is a proper Dantesque selva oscura, full of undercover art advisors, transactions between anonymous parties, and stoical gatekeepers who work hard behind the scenes to keep their interests safe.

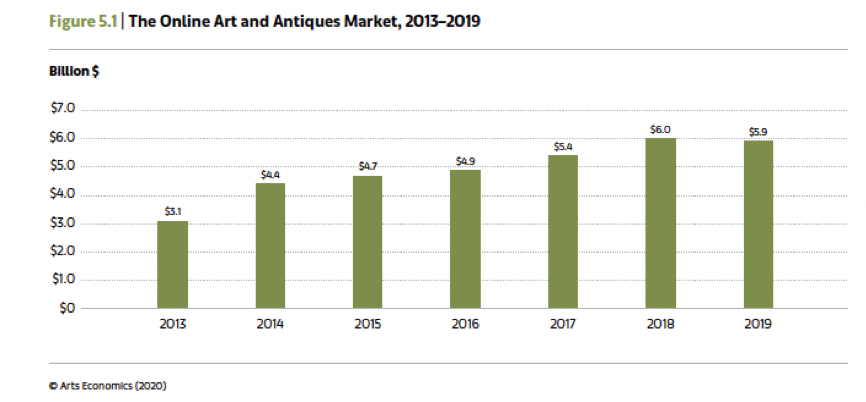

The centuries-old art market has proven to be extensively resistant to innovations, however, even its most conservative players had to acknowledge the increasing relevance of the digital space. According to the Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report 2020, the online art market has been thriving for the past five years, accounting for $5.9 billion in 2019, but its growth rate is slowing down, with lack of trust and transparency as the main attributable factors.

Source: The Art Market Report 2020, Art Basel & UBS

Most certainly, the snapshot of the online art market will look completely different in next year’s reports, as the coming of the global pandemic forced all the market players to move their entire businesses into the digital space. The digital realm has always been seen as complementary to the offline art market, made by private viewings, VIP programmes and collectors’ lounges. However, due to the absence of the physical art world induced by the pandemic, the online world is currently the only available one. Indeed, the COVID-19 outbreak provoked a forceful boost in the development of online platforms and having a strong e-commerce has become the key to keep the sales on an economically sustainable level.

A noticeable change happened in the art fairs sector, which has been obviously highly impacted by the pandemic and its consequent travel bans. Art Basel Hong Kong online viewing rooms debuted at the end of March, paving the way for the shift from offline to the virtual world. I remember looking at the “booths” of my favourite galleries, and then only later noticing tiny numeric digits just below the artworks: prices. Price transparency in the context of an art fair is something that you don’t frequently see even in “live” editions, where sales people are often trained to politely decline to declare price ranges. Art Basel Global Director, Marc Spiegler, explained in an interview that the decision of including prices has been made after careful consideration of whether this could have been a winning strategy to encourage and speed up the acquisition process. A few weeks later, Frieze Viewing Rooms New York followed in persuading its participants to make prices publicly available and, according to its New York Director Loring Randolph, the missing face-to-face interaction with potential collectors can be overcome by tearing down as many barriers as possible. You can listen to ArtTactic’s podcast with Loring Randolph on this topic here.

In the midst of the enthusiasm for this sign of further democratisation of a well-known elitist industry, we all have lost sight of what could be a real game changer in the long term, that is the unprecedented availability of user data from the primary market. Indeed, when we consent to the use of cookies we are giving permission to the website owner to track our movements within the website, what items we click on, and the amount of time we spend on each of them. This information becomes incredibly valuable as they form what the Harvard professor and writer Shoshana Zuboff calls “behavioural surplus”, meaning that this data gives insight into consumers’ behaviour and, consequently, can be used to predict – and to influence – the market of the future. Apparently, the upcoming virtual edition of Art Basel will provide its exhibitors with this kind of analytics that will allow galleries to perform quantitative analysis and to understand which artworks received the highest number of views or which ones induced tangible actions. Moreover, platforms such as Art Basel and Frieze online viewing rooms require visitors to log into an account or to provide personal information like full name, phone number and email address. Consequently, art dealers now have all the ingredients to create identifiable individual profiles that outline the user preferences and that could be used to implement personalisation engines.

It is too soon to say whether the art market is ready to strategically benefit from the behavioural surplus, but it is for sure acknowledging that data availability can be turned from being considered as a threat to becoming the most valuable asset. A question that might arise and that would deserve further speculation is whether – in the context of a demand-offer logic – raw data from the primary market will ultimately influence the production of artworks, and therefore our contemporary culture itself. Only time will tell.

Olimpia Saccone is a London-based art business professional specialised in communications and business development within the sector. Olimpia earned a Master’s degree in Art Business with distinction from the Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London where she also was a guest lecturer for the semester course Art of the Luxury. Following her research interests in the art market ecosystem and in the artists’ career trajectory, Olimpia worked for a talent agency for emerging artists as a business development manager, and she was in charge of commercial partnerships. She is currently advising emerging artists shortlisted for the Ashurst Emerging Artist Prize and she is a contributor to LVH Journal. Olimpia is a member of The International Art Market Studies Association.