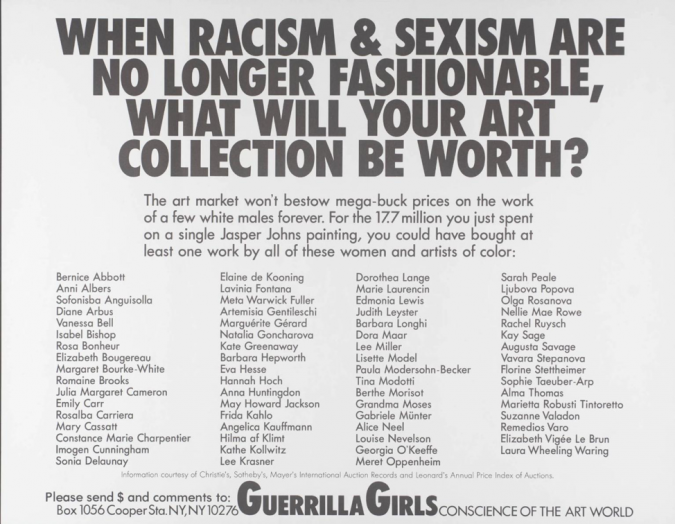

Guerrilla Girls, Guerrilla Girls Talk Back © courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com and part of the Tate Collection

Several years ago, I realized that the art world had a major problem.

In my fourth year of studying as a fine artist at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I decided to sign up for a new extracurricular course titled “Art and the World of Big Money”. The course was taught by a part time teacher and director at a big gallery in downtown Chicago and focused in giving students a comprehensive understanding of the structure of the art market. Fifteen minutes into our first lecture, the professor began to create a diagram on the dry erase board depicting “The Life and Career of an Artist”.

Drawing that diagram took him roughly an hour. He went through all the motions: starting the “artist” off at undergraduate art school, followed by graduate art school, suggesting that the artist utilizes this time to build and refine their practice. He demonstrated that the next step for the artist’s career is to be picked up by galleries that either find the artist through solo and group shows, exhibitions, and even sometimes press. As the artist progresses and their networks’ expand, these galleries would also gradually get more established over time, became more global instead of local, and more art world players would be added to the scenario: such as art critics, writers, collectors, buyers, institutions, and even auction houses.

All of these variables help create name and brand recognition for the artist over time; the step in the process is to eventually end up in major museums and cultural institutions. Eventually, the end of the diagram leads to the artist’s death, and, following the artist’s death, that career can be brought even further through legacy, foundations, and ultimately, a permanent place in collections and history.

As a developing artist myself, I sat there a bit overwhelmed as I stared at a literal template for a future that could be mine.

I didn’t think about anything else until a peer to my right, who had been feverishly jotting down her notes the entire class, raised her hand and asked, “What happens if the artist isn’t good?”

Without hesitating, the teacher blatantly responded, “Oh, that doesn’t affect much”, implying that you don’t necessarily have to be a good artist to successfully follow this trajectory. With the right connections and the right amount of funding, any artist can technically become a well-known artist.

This floored me at the time. Ultimately, it confused me that any artist with enough of a network could flow with ease through this formula and theoretically end up in a major collection somehow. Here I was, trying to be the “best” artist I could possibly be, spending sometimes up to ten hours a day honing my practice in hopes that, if I spent enough time, it would eventually lead to the outcome of a “good artist” and therefore, a “successful artist”.

This was my wakeup call that this was not always the case.

Today, my commentary is not about “good” or bad” art, as I have come to accept that art is often subjective. Rather, I am addressing the system that fuels the art industry, the people who run it, the actions they take to help make the system the way it is, and question my own active participation in it. It’s no secret that the art world has been mythicized by its “Wild West” rules and regulations, lack of transparency, Big Money, and strict adherence to the status quo. But due to recent events (a worldwide pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement – just to name a few), these disparities have been highlighted. I wonder, is there room for the art world’s antiquated systems any longer? Is the art world out of touch with reality?

Call to Action

The past month, in particular, has been a critical time for many institutions and art brands to reevaluate their role in not just the art world, but in the world at large. For instance, the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), which has been reignited in the United States following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of four police officers in Minneapolis, is not just an American issue, nor just an issue of police brutality. More people around the world are beginning to wake up and realize the deep-rooted, systemic flaws within their institutions. These monumental movements demonstrate the criticality of our voices in society. Especially in a time like this.

Art that Critiques Its Own Industry

This call for change is not new. Artist activist groups like The Guerilla Girls have been making work specifically about these disparities in the art world since as far back as the eighties.

The anonymous group of female artists are notorious for creating satirical, yet factual, public art that exposes gender, racial, and systematic inequalities within institutions and its patrons. In an interview conducted in 2015, Frida Kahlo, a member of the Guerilla Girls who has hidden her real identity by adopting the title of one of the great female artists from the past, asked the rhetorical question, “If museums fall into that system of collecting the most expensive art and being all about the art market, is that really telling the story of production of our culture? I don’t think so, because if you look at that, billionaire art collectors are running the show, and they are a very homogenous group. They are far more homogeneous than artists are”.

The Guerilla Girls outside of Whitechapel Gallery. Photo: © David Parry (from www.whitechapelgallery.org)

New groups, like the New York based Artists for Workers (AFW) follow the same mindset. AFW has recently formed in 2020 in light of some museums’ responses, or lack thereof, to the BLM protests and political turmoil. “Different crisis, same commitment to the status quo” is read on countless posters that have been plastered onto the walls of boarded up museums during the protests in New York. Many museums and art brands have been put on blast for their elitist-driven attitudes and alleged ignorance to major social issues, such as allowing racism and sexism in their work culture.

The artists and art professionals who challenge their own market have increased in popularity during this time, particularly through their social media and online presence.

Rethinking the Definition of “Cultural Institutions”

While some were criticized for staying quiet for too long, many major cultural establishments, patrons, and brands began speaking out in solidarity of major social issues and even going as far as addressing their own mistakes and past wrong-doings.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (MCA), was recently criticized in 2019 when a photo was exposed of their close ties and donations to the Chicago Police Department. Due to recent protests and petitions, however, the MCA publically announced in early June that they would cut ties with police until reforms are made to the Chicago Police Department. The MCA was the third largest major art institution to cut ties with its cities police department, along with The Walker Art Center and The Minneapolis Institute of Art in Minneapolis.

A myriad of announcements like the MCA’s go on:

On June 23, Melissa Chiu, Director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C, announced new initiatives to change and implement new methods of operations. “We are responsible for supporting and building an equitable society within and beyond our walls”, Chiu says, in an effort to announce a new way of thinking as a cultural institution.

The Tate networks even publicized the data on its own demographics of its workers after issuing a statement that addressed the power of their own platform and influence as a voice in the community.

Aside from admitting flaws, galleries and museums have also taken the opportunity to promote and post more socially aware content in tandem with the current BLM protests and political turmoil.

A collective of major international institutions such as the Tate, Palazzo Grassi, and Stedelijk Museum, collaborated with the American Black artist, Arthur Jafa, to live stream his 7-minute video “Love is the Message, The Message is Death” (2016) for 48 hours over the weekend of June 26. The video itself serves as a powerful message on racism and black resilience.

Galleries, like Superchief Gallery, based in New York City, Los Angeles, and Miami, have completely dedicated its efforts to helping support BLM and has become an active participant in spreading important information. “WE ALL NEED A CHANGE IN LEADERSHIP”, they wrote on an Instagram post, accompanied by an IGTV video of an activist discussing the governments denial of systematic racism. Posts regarding their own artwork at the gallery have not been seen for weeks.

While the sentiment behind the increasing number of statements and calls to action to “do better” have been astounding, they have also come with their fair share of backlash, and for a good reason.

The real change comes with time and critical action.

You Say You Can Change: Now What?

With any change, comes opportunities for growth and improvement. We cannot keep this momentum without continued internal reflection and critically acting on it.

We must constantly acknowledge that the art industry directly benefits off of statements that artists have made, political or not. These artists, as well as the greater public, look to our cultural institutions to spark innovation for change, progressiveness, and creativity. We must do better.

We, as thought-leaders, as a community of art lovers and statement makers, have an important role to play. The art world will not move forward unless we right our wrongs. Addressing our own problems is one of the hardest things to do, but our words ring hollow if we do not do so.

Mattie Martinez is an American artist and art industry professional. She received a four-year merit scholarship from the leading American arts university, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she received her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting and Visual Communications. Following her Bachelor’s in Art, Martinez became increasingly passionate about the art industry itself, and gained a Master’s degree in Art Business from Sotheby’s Institute of Art in London. There, she completed a dissertation which researched online marketing techniques within the Art World and analyzed the industries’ utilization of social media platforms such as YouTube. Over the years, Martinez has also worked with a wide variety of art institutions and companies in major cities such as Chicago, London, and New York.