Image from Art Forgery: Why Do We Care So Much for Originals? (Medium)

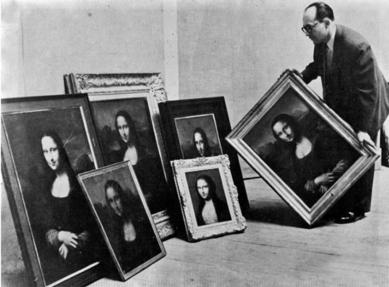

When assessing the current status of the art market, it is worth remembering that around twenty to fifty percent of the works in circulation are fakes, forgeries, misattributions and unknowns. Some studies that startled me indicated that one artwork out of ten held in museums are fake – and that’s without taking the enormous number of misattributions into consideration.

In the challenging environment we are currently navigating, an increasing number of high-value transactions are taking place online, often with the artwork purchased sight-unseen (only from images on a screen). When a collector spends a significant amount of money on a work of art, this poses a real and substantial risk – asking for additional reassurance is not only a fair request, more robust support becomes almost a requirement. But what pieces of information or data points really matter when determining if an artwork is genuine and if it is in good condition when buying – and, maybe more importantly, to potentially enhance its value if one is selling? An information package that includes provenance and technical art history is very advantageous when seeking to obtain a connoisseurial opinion or to bring a work to sale.

Provenance.

The provenance of a piece is a very important component in determining its authenticity. It is also one of the biggest drivers of an item’s worth, but it needs to be investigated seriously and with some skepticism. Too often, I see clients so enamored with an artwork that they are blind to its more dubious features, convinced for instance that any documentation related to the piece that they have been given or received is accurate, or, that the fact that certain documents are missing is immaterial. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. One artwork we investigated was a painting thought to be by Heinrich Campendonk, which turned out to be made by the German forger Wolfgang Beltracchi, who faked provenance documents along with paintings, in order to make his pieces more credible. It is sad to say that his efforts to deceive were not readily discovered and subsequently sold for millions at reputable galleries and auction houses.

Provenance can also be incomplete or in some cases missing, in parts or in its entirety. One important point to keep in mind is that provenance comes in many different forms: from signed statements of authenticity to sales receipts, artists’ archives to exhibition records. It is rare that all of this information is preserved – especially for older pieces.

When there are gaps in the provenance, we often see this as a red flag, as it indicates the greater possibility for problematic issues: misattribution, forgery, sometimes theft. However, in lucky instances, the piece in question may be found in the artist’s catalogue raisonné (if one exists) – which is, in theory, the most complete documentation of the artists’ production. Many times, catalogue raisonnés are few and far between, and are often reserved for those artists who are internationally recognized. What about the less fortunate or lesser-known artists who have not had their works documented in this manner?

Science and Technical Art History.

For a very long time, post-modern approaches to art history did not consider the artwork as a material object. Consideration of technique and material composition of works of art was not considered to be useful.

In light of the current lockdown situations world-wide, which prevent many connoisseurs and potential buyers from travelling to see art in person, art market participants are finding alternative ways to sell their pieces, and in doing so, are slowly embracing new technologies that allow them to collect more information. This provides the dual advantage of knowing that what they are selling is authentic while maximizing the value of their sales. At Art Analysis & Research, we have been offering such services for more than a decade and are just now finding ever more acceptance of the value that analysis of the artwork can offer. Our scientific approaches use newer technologies to examine works of art, providing evidence-based information on the history of the piece, its dating, attribution as well as on condition.

Our experts have spent decades collecting and analyzing data on an extensive range of reference materials, especially pigments – our database of pigments is the world’s largest, privately owned collection as is its associated spectral library! As a result, we are able to refer to this rich historical data, ensuring that our results are accurate, consistent and comprehensive.

Technical analysis may be applied to all sorts of media, ranging from paintings to sculptures, to drawings and more. We undertake pigment analysis, technical imaging, material identification and carbon dating to cite just a few. Our aim is to provide a range of techniques and the historical context to make them meaningful in order to help collectors increase the value of their pieces and the buyers decrease the risk of buying forgeries, misattributions or highly restored objects. A recent example is our work for Dickinson Gallery for TEFAF 2020, for whom we provided the technical imaging for Vincent Van Gogh’s “Peasant Woman in front of a Farmhouse”. The x-ray revealed an abandoned composition underneath the visible painting, which corresponded with a known drawing by the artist. The work was eventually sold by the gallery for a TEFAF record-breaking price of €15 million!

Provenance research and technical art history are key first steps. Once done, it’s the right moment to approach a specialized connoisseur for their opinion. The order of these steps is important, as a connoisseur benefits from having as much objective information as possible regarding a piece to give the best opinion – which can often make or break the reputation of a work of art. An information package that includes both provenance research and technical art history provides the most secure starting point from which to obtain a connoisseurial opinion or to bring a work to sale.

Connoisseurship.

The role of the connoisseurial expert is to determine when, how and which artist created an artwork, by looking at the stylistic characteristics of the piece along with other key information. Nevertheless, there are many factors at work in this opaque market; legal risk, reputational risk, market dynamics, personal influence and other unforeseen aspects often play significant roles. That said, this is not to imply that connoisseurs, dealers, or others in the market are working in bad faith – but rather they often have a multitude of pressures and considerations. Isn’t it better to have more information available to the connoisseur, and subsequently to dealers, gallerists, advisors and others to equip them with more authority in evaluating or representing the work?

A few years ago, a newly discovered painting thought to be by Wassily Kandinsky was brought to our lab upon the request of the Kandinsky Foundation, to provide an assessment to assist the artist’s foundation in reaching a decision on the authenticity of the work. After conducting a technical examination, we found the painting to be consistent with Kandinsky’s materials and with technical imaging, were able to decipher an underdrawing that depicted a harbor scene. The Foundation discovered the underdrawing matched a sketch done by the artist in his authenticated sketchbook and, thanks to this discovery, the painting was accepted into the catalogue raisonné. Needless to say, its value increased enormously. This is just an example of why we have seen the power and value of embracing new ways to investigate artworks.

The Future of Authentication.

Opaque and unregulated, the art market has long been vulnerable to forgeries and misattributions and the number of fakes will undoubtedly increase due to the new tools available to forgers. From using old canvas or adding some cracks that would make one believe the work is from a specific artist’s period – it is becoming increasingly difficult to keep one step ahead of the forger. And in the challenging environment we are navigating with many transactions taking place without seeing the artwork first, authentication is becoming increasingly more important.

If you ask me what makes technical art history so powerful, I would say it is the multidisciplinary approach that fuses science and art together. It is incredible to observe first-hand professionals with backgrounds in conservation, art history, physics, forensic science, engineering and business all working together. This sort of collaboration is what I hope for the future of the art market. Collaboration is the way forward; we all have our areas of expertise and working together is the key. Collaboration is powerful and perhaps most importantly, beneficial for the buyer, the seller, and the various professionals involved.

With the help of science, art history, provenance research, connoisseurial expertise and an open mind to new technologies, I am convinced that together we can create an art market that is less risky and easier to access for future generations.

Dehlia Barman leads customer and partner engagements in the UK and Europe for Art Analysis & Research previously working at galleries, auction houses, online art businesses and art advisory companies. Dehlia also guest lectures at Sotheby’s Institute of Art and Regent’s University, delivering sessions on the importance and value of art authentication. Her journey in the art world started in Lugano, Switzerland where she completed a bachelor’s degree in Communications. Passionate about the dynamics shaping and influencing the art market, Dehlia moved to London and completed her MA in Art Business at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art.